|

| Benny Harris playing with Bird, Diz and others c. 1950 |

3- Interlude

Studies 1968-69: Bach, Latin, Booker T, and some One-Shots

TONE-DEAF! – One of the first things I did after the Cosmic Pimps broke up was to look for another band. I played with several informal groups for a week or two each. They were more jam sessions than actual bands.

The one with the most impact was led by a virtuoso guitarist (another forgotten name) who had studied at the famous Juilliard School in New York. He had amazing dexterity on the guitar; he could play melody and simultaneously supporting chords or bass-lines.

He gave me a ‘wake-up call’ which set my life for the next year. He showed me that I was tone-deaf! He proved it by playing G octaves on his guitar over and over, and I was unable to find his G on my keyboard, even though he played it over and over! I think was part of my semi-autism, shutting me off from the outside world in a protective shell.

This made me immediately look for a music teacher, which led to my studies with Javier Castillo, the first person to start systematically working on my musical hearing (as well as my nerves – see below). After Javier I bought some ear-training books, and in the mid-70s studied ear-training intensively as part of my lessons with Charley Banacos (see Chapter x). Around 1978 – ten years after I had discovered my tone-deafness, and so spent those ten years on ear-training exercises with both teachers and ear-training texts – my musical hearing had gotten so good that I was able to learn the Steely Dan song “Deacon Blues”. I was able to hear and write-out for a client all the parts of this rather difficult piece: vocal melody, bass line, chord progression, and harmonic structure of the chords. I gave myself a pat on the back then: who wuldda thunk that tone-deaf Lee could transcribe all the parts of one of Steely Dan’s toughest pieces! I continued doing a few minutes of ear-training as part of my daily practicing throughout my music career; because a good ear is like a strong body – you can lose it if you don’t work on it every day!

Looking as usual in the underground press ads, I found JAVIER CASTILLO, the first great teacher in my adult music career. Javier was a wonderful guy - warm, compassionate, and brilliant. His approach was to focus on the main area where the student needed work: in my case, that was being very nervous playing in front of others, resulting in shaking arms. (I didn’t have this problem with free jazz, since no one could tell what was right or wrong). So Javier gave me a set of exercises to train me to drop all control completely and let my arms swing down via gravity: he called these "dead arm exercises."

Twenty-two years later, up in Seattle, one of my first students there was a junior high school girl who had been raised in such a genteel fashion that her

arms were almost literally frozen with politeness, so that she went around with her arms wrapped in brown elastic bandages. So I taught her the Javier exercises as well as a couple of my own (mainly 'Bombs Away!" = the student holds both arms one foot over the piano and lets them fall = and then the standard free jazz keyboard pounding as loud as possible). Sure enough, in a couple of months she was liberated from her bandages and playing keyboard with power and finesse. The last I heard from here, she had taken up flute and was playing with her high school band on a trip to Moscow! Her parents were very grateful to me, and helped me establish my Seattle studio. Which means, of course, that it all went back to Javier C.

Once I was 'cured', Javier kept me on a steady diet of Bach, Mozart, and Afro-Cuban montunos. I got to see him perform once with a friend's Afro-Cuban combo at the Fillmore West. The last time I saw Javier was when I briefly visited Berkeley in 1972 and said hello. I don't know what happened to him since then, but I will always be in his debt (not to mention my Bellevue Washington jazz debutante!).

Javier printed a booklet of samples of montunos and other basic of Afro-Cuban music theory. Three pages of my copy have survived the half-century – and insect and rodent attacks in Luzon – and I am including them here. This was my foundation, and enabled me to play in norteno and mambo bands in LA, and to create my version of ‘Sofrito’, a classic Latin jazz piece by Mongo Santamaria. This piece has gotten by far more views than any other clip on my YouTube music site. So if you are a keyboardist who wants to play Latin jazz, practice these three pages over and over and you will be happy with where this takes you.

Sofrito - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XOrWeZOaWDg

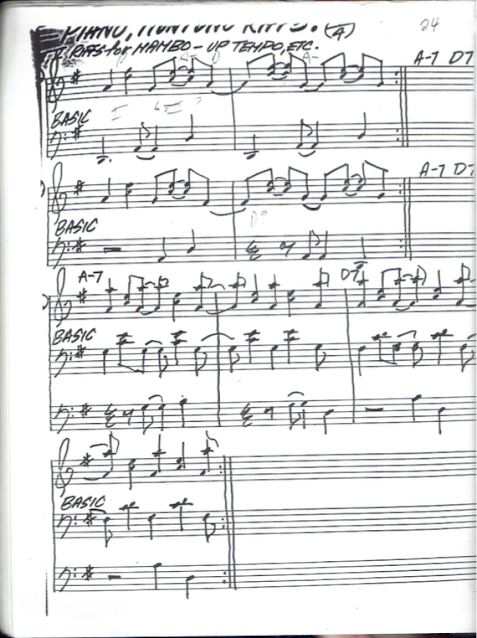

(The three music pages below copyright Javier Castillo, 1968)

FIRST STEP IN AFRICAN-AMERICAN MUSIC THEORY – For a few weeks in 1968 we had a next-door neighbor who was a semi-professional R&B guitarist.

He gave me my first lessons in blues theory – first, the basic 12 bar blues; and second, avoid the leading tone at all costs when soloing. He put it like this: “you can play any note in a blues solo and make it work – except for this one!” And he forcefully pressed down on ‘B’ (the seventh note of the C major scale as an example: he meant in any key, avoid the seventh note of that key.

Since the move from tonic (1) to leading tone (7) and back to tonic (1) is the core movement in European classical music from around 1500 until 1900,

and even after that is the core movement for basic conservatory music theory,

one can see how this ban on the 7th note for African-American blues, gospel and folk music would helped create a whole new theory and approach to music.

At the time, I didn’t know this context or really much of any music theory – but I played avoiding the melodic 7, composed melodies avoiding the melodic 7, and by mid-1970s finally understood the significance of this ‘ban,’ [For more, see Appendix 1: Afro-American, Afro-British, and Afro-Romantic]

ENTER THE BLUES SCALE - Later I took a few lessons with the keyboardist from a rock/bossa-nova group, "Gail Garnet and the Gentle Rain." In a few lessons he taught me how to play a blues scale, the basis of most rock improvisation at that time and later. With the minor blues scale ( = minor pentatonic with a couple of added chromatic notes) I could solo on almost any rock, pop or R&B tune. Once when I was practicing improvisation on my Hammond M-3 organ, two young Black men were moving some furniture we had sold out of our house, and one started dancing to my little tune. "Why are you doing that?" one asked the other. "Hey, it makes me feel good to hear that groove." I was thrilled, and decided to look for work in a rock band.

AUGUSTUS LEE COLLINS – Augustus is a virtuoso drummer from Oakland. Still a teenager when I met him, he had one of the most technically dazzling styles I ever heard on a drumset drummer, then or now. He was small, thin, jet-black, with a very sharp mind – a miniature Black genius!

We played together briefly in a black heavy metal band, the Metropolitan Sound Company. The band was good enough that Clive Davis, the leading rock scout for Columbia Records, came to our Marin County practice room to hear us. Unfortunately, we were determined to be louder than any other rock band in the area – and unfortunately, we succeeded! At our very first chord Clive fell to the floor, clamping his hands over his ears and screaming “Stop! Stop!” (I am not making this up). And that was the end of that!

Augustus and I continued our friendship long after the band broke up. One time we were watching one of the outdoor rock-jazz concerts that were so common then in Berkeley, and Augustus gave me the one observation of him that I still remember: “Lee, when I see another drummer, I don’t ask if he is better or worse than me. I just want to know, ‘what is he doing that I can use?”

A most valuable piece of advice, and an approach to listening that I have followed ever since.

According to the Internet, Augustus was still be playing in Oakland in 2009 – I found the following notice via Google Search:

This Sunday, May 17, 5 p.m., at Shashamane’s Ethiopian Restaurant and Lounge, 2507 Broadway, downtown Oakland, Unity Concepts will begin its first and third Sunday of the month poetry and music showcase, Oakland Is Speaking, hosted by Oakland born poet and recording artist Paradise Freejahlove Supreme. The event will feature local legend Augustus Lee Collins and his rhythm and blues band, M-Pulse … “

MY LAST BERKELEY LESSON: ‘LITTLE” BENNY HARRIS

Benny Harris was a bop trumpet player and a composer. He composed or co-composed (with Charlie Parker) the bop classics “Crazeology”, “Ornithology”, and “Reets and I”. In the 1940s and early 1950s he was a major participant in the famous jazz scene on 52d St (New York), played with many of the bop greats, and is credited with having introduced Parker to Dizzy Gillespie. He played and co-composed with many other leading figures of the time, but stopped recording around 1952.

I ran into him in 1970 when I was already playing with Chambray.

I picked him up hitch-hiking, and when he found out I was an aspiring musician, he insisted on my driving him to the Chambray house (where my keyboard was). First he tried singing me lines to copy – the African-American

oral tradition. But I had just started working on my ears, and was still too tone-deaf to pick up what he was singing. So he wrote out two pages of compositions (copies below), and urged me to learn them. Then I gave him a ride back to his room in San Francisco, and never saw or heard from him again. Benny Harris died in 1975. Here are these pages for any who would study them (in 12 keys of course).

ENTER FROSTY - Once again turning to advertising in the underground press,

I got an immediate response from Forrest "Frosty" Furman. Frosty

was a fanatic devotee of the Memphis/Stax-Volt sound of Booker T and the MGs. In particular of the clean and funky guitar of Steve Cropper.

Booker T and the MGs were an integrated quartet - Booker on organ,

Steve on guitar, and a White bassist (Donald Duck Dunn) and a Black drummer (Al Jackson Jr). They combined the utmost precision of playing with a powerful R&B groove. I was familiar with their most famous hit 'Green Onions,' but Frosty immediately turned me on to their whole repertoire. Combining my new knowledge of blues scales and more disciplined classical lessons from Javier, after a few months of playing I got to be around as good a Booker T. imitation as there was in the Bay area back then.

Frosty kept encouraging me to follow this sound. He dismisssed most rock groups, no matter how famous, as being sloppy and un-funky compared to the Memphis crew, and kept pushing me and encouraging me to move in that Booker T. direction.

At that time Frosty was a fairly radical Berkeley cat - I once had to hold his arm back from throwing a rock at a police line charging a Berkeley demo - but still had a lot of conservative thinking. "Right OFF', he liked to scoff. He had put together a quartet and we did a lot of practicing but hardly any performing. After a few months Frosty moved to Wyoming and the Mountain states. Frosty was always an athlete, and loved to ski, which made this a good place for him. And he also got deeply influenced by country rock as well as classic rock n' roll - his two favorite groups then were the Band (Dylan's country rock group) and Chuck Berry.

ENTER CHAMBRAY AND THE COCKETTES - I stayed in touch with Frosty with the occasional phone call, but right away went into playing with Chambray. Booker T. style organ was just what Chambray needed to counterbalance their high energy, not quite in tune Bay area rock groove, and soon Chambray started to climb the ranks of Bay area bands. After around a year, Frosty called me and said he was going to study music in Boston with some of his country band friends, and asked me to join them.

This was around a year after I had been playing with Chambray, and I decided I was ready to move on. I had gotten swept up in the fun and fame of being a star in a Bay area rock band, and realized that if I didn't leave Berkeley soon, I was going to burn out on parties, drugs, and more sex than I could physically handle. I had been reacting to my socially isolated, semi-autistic teenage years, and now that party time was open to the max there was no way I could say no when getting a phone call inviting me to drop by to savor some great smoke with some beautiful boys.

So I decided to bite the bullet, say farewell to my wonderful rock and party life, and join Frosty in Boston.

Before moving onto the Frosty/Boston experience, let me go a little deeper into what happened when the hard country rock of Chambray combined

with my gay friends in San Francisco, notably the Cockettes. As a result, Chambray had a dual base - straight country hippies and the Cockettes' San Francisco gay family - and this multiple fan base started moving Chambray up the Bay area prestige scale. We were all the way up to the second highest level of clubs - the Family Dog by the Great Highway, second only to the Fillmore itself - and might have gone further, but my physical body most likely would not have survived it. I could feel my heart weakening, and passed out once on an acid trip to a Nevada Indian desert reservation with my Cockette Amerindian lover Link. So, most reluctantly, I told Chambray goodbye, sold my Hammond M-3 and it was 'please come to Boston' time for Lee Cronbach.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Comments

Post a Comment